Sarah Knows Eyes

Okay, so the title may be a little overdramatic and not strictly true, but it stems from a conversation I (unwittingly) overheard in practice the other day that peaked SarahKnowsEyes curiosity – I had to investigate further! Delving deeper, I discovered a fascinating and gruesome tale that I couldn’t wait to share with you all (aren’t I nice?!).

Johann Sebastian Bach

In 1749, at the age of 64, it is safe to assume that Bach’s vision had deteriorated naturally with age, he was undoubtedly presbyopic and hence required some form of magnification for reading, but it would seem that he had also developed cataracts, at a reasonably young age it has to said. (Of course, he could have been born with them, but I’m going slightly off at a tangent now…)

Although it would appear that cold hard facts are somewhat difficult to come by, we do know that Bach had either one or both of his eyes operated upon during the final days of March 1750 by a traveling British eye surgeon, or "oculist", the (self-appointed) Chevalier, John Taylor, and that at least one (possibly both) had to be operated on again a week later. This second operation left Bach totally blind. He was blind when he dictated his final work (The Art of Fugue), and he died a few months later on the 28th July 1750, from what was described as a “painful eye condition”.

More than two-and-a-half century's later, prominent Finnish ophthalmologist, Ahti Tarkkanen1, offered what he called a “plausible diagnosis” of the great composer: “Because Bach was blind after the second operation, and suffered from immense pain of the eyes and the body, the symptoms could be compatible with acute intractable secondary glaucoma.” It is also possible that the procedure may have caused retinal detachment(s). It is notable that Tarkkanen refers to Taylor as a “surgeon” in quotation marks, giving you some idea of his lack of respect for the practitioner.

Chevalier John Taylor

Daniel Albert2, the author of Men of Vision, a history of ophthalmology, calls Taylor “the poster child for 18th century quackery” noting that he “practiced in the most flamboyant way, drawing crowds to watch procedures in the town square, and then getting out of town before the patients took their bandages off." In fact, an entire chapter of his book is dedicated to Taylor's colourful, if somewhat gruesome, career. He describes him as "the most infamous of all ophthalmic quacks." His arrival into town would be heralded by placards and handbills, and his coach was decorated with paintings of eyeballs and the motto: "Qui dat videre dat viver" (He who gives sight, gives life).

This just makes me think of James Franco’s Wizard of Oz, in the 2013 film “Oz the Great and Powerful”:

.jpeg)

Taylor performed a “couching” on Bach, which is the oldest (dating from 2000 B.C.) and crudest form of cataract surgery. It involves dislocating the cataract lens with a sharp or blunt instrument,such as a needle, which is poked into the eye to effectively push the cataract-clouded lens back into the posterior chamber, out of the field of vision.

.jpeg)

/via www.bioline.org.br

At the time, physicians had no concept of bacteria, and no anaesthesia, so the idea was to operate as quickly as possible. "If you had a good result a third of the time, it was par for the course," Albert says of 18th century techniques: "People didn't expect a good outcome; they knew if they put themselves in the hands of an eye surgeon, they were taking a big chance." Of course, the risks may have been greater with a charlatan like Taylor…

Whilst there is no obvious cause-and-effect relationship between the operations and Bach’s death, Taylor’s postoperative care regime reads more like torture, by which the Orion Syndicate seem like pussy cats in comparison?! It included the use of eye drops of blood from slaughtered pigeons, pulverized with either sugar or baked salt, whilst in the case of serious inflammation Taylor prescribed large doses of mercury. In a 2005 paper examining the same subject, physician Richard Zegers3 notes that “the operations, bloodlettings, and/or purgatives would have weakened him and predisposed him to new infections.” Ultimately, a post-operative infection is the most likely the cause of Bach’s death.

Perhaps most tragically, a more modern method was being tested in a neighboring nation. In 1747 – three years before Bach’s operation – Paris-based ophthalmologist Jacques Daviel conducted the first cataract operation using a new, safer, more effective method. His “extracapsular technique” would soon become the standard procedure for cataract operations, and remain so until the early 20th century. Today, surgeries in which cataracts are removed and the lens replaced are among ophthalmology's most successful procedures.

Sadly, it was too late for Bach, and seemly so for another great composer of that era, George Frederick Handel. In 1751, he, too, underwent the surgery, several times, probably the last one at the hands of Taylor– and, like Bach, none of the surgeries worked and he was left blind. Poignantly, the lyrics to “Samson": "Total eclipse. No sun, no moon, all dark." – were written as Handel's eyesight failed.

George Frederick Handel

Wowsers! Let’s just say it makes me thankful that medicine has moved on somewhat since then! Or has it…

I was shocked to learn that this procedure is still in use in some parts of Africa and India! Tarkkanen points to a 2009 study from Sudan that examined the ultimate outcome of 60 contemporary couching patients. It found 60 percent of them were totally blind, due to glaucoma. Frightening!

Bibliography

-

Tarkkanen, A. (2012). Blindness of Johann Sebastian Bach. Arch Ophthalmol. Mar; 91(2): 191-192.

-

Zegers, R. H. C. (2005). The Eyes of Johann Sebastian Bach. Arch Ophthalmol. Oct; 123(10).

-

Albert, D. M. (1994). Men of Vision: Lives of Notable Figures in Ophthalmology. Saunders

And special thanks to:

Susan LambertSmith (http://www.med.wisc.edu/news-events/handel-bach-were-blinded-by-18th-century-quackery/25951) and Tom Jacobs (https://psmag.com/why-did-bach-go-blind-5957636c6b41#.gc62182b7) whose articles made for such an inspiring read, and made this blog post possible!

Write comment (1 Comment)

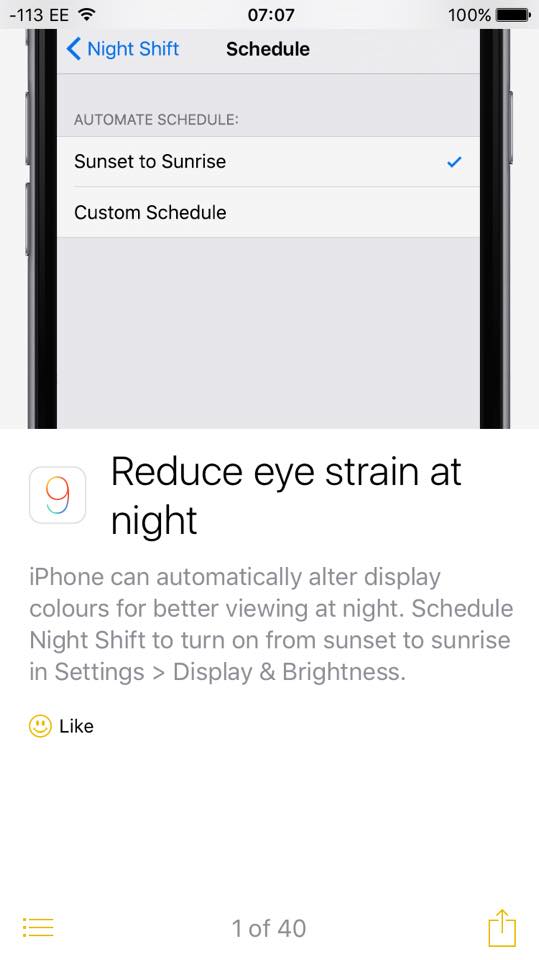

Finally succumbed once all the "the new update is evil" fracas abated, and updated to iOS 9.3.1. This is an interesting little feature, especially following SKE March blog...

P.S. I've set it up and love it BTW! #NightShift

Happy Easter peeps! Don't eat too much chocolate!

/via https://www.pinterest.com/luxuryeyesight/animals-glasses/

Write comment (0 Comments)

Conveniently following on from January’s Dry Eye “lecture” (sorry about that!), and having been asked about this particular topic on more than one occasion following the SKE “Movember” movement, it seemed like the perfect time to reiterate a few points I’ve made about computers and your eyes. Well, computers; phones; tablets; TVs; handheld gaming devices; the list is positively endless…

Basically, anybody spending a significant period of time (two or more hours) using any form of digital device, be it for work or play, is putting an enormous strain on their eyes.What most people don’t realise is that when looking at these screens, our eyes become somewhat “fixated”...

This not only effects our blink rate and the quality of the tear film, which can cause Dry Eye (as discussed in last months blog), but can also lead to Computer Vision Syndrome (CVS), symptoms of which include eye strain and/or headaches, light sensitivity and double vision.

Remember the magical 20:20:20 rule – every 20 minutes, look away from your screen to a distance of approximately 20 feet for 20 seconds!

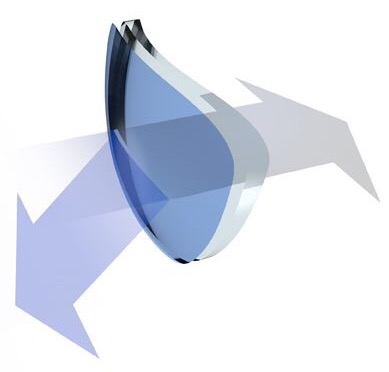

Perhaps most importantly, make sure you have your eyes tested regularly (at least every two years) and if you are advised to wear glasses for VDU use, etc - WEAR THEM! If you do, you may benefit from an “anti-reflective” coating. This reduces the amount of glare and reflection from such media (and overhead “office” type lighting) in order to improve acuity and contrast. (They are also useful for those people bothered by car headlights when driving at night!).

A hot topic in optics at the moment is “blue light” which is emitted from the likes of VDU screens, tablets, smartphones etc, over-exposure to which has been demonstrated to be a major factor in digital eyestrain, eye fatigue and even sleeplessness. 'Blue controlling' coatings work to selectively absorb/neutralise this harmful blue light, keeping it from entering the eye through the cornea and reaching the retina at back.

Image /via stufkenoptiek.nl

Slightly off at a tangent, but I recently read an interesting article about the role of light in promoting wakefulness, find it here, but the upshot of it is that even small electronic devices emit sufficient light to miscue the brain and promote wakefulness, disrupting the natural pattern of the sleep-wake cycle. The general advice would seem to be remove any and every light emitting device from your bedroom, which seems hugely impractical, and I’m not saying that there’s a link between the blue control coatings and a better night’s sleep, but for any insomniacs’ out there, it can’t hurt to try, right?

As with everything, there are downsides. Coated lenses in general are notoriously difficult to keep clean, and pragmatically are more beneficial to short-sighted, as opposed to long-sighted people.

I actually have a pair of these coated lenses, and I do think they work. They can be applied to a person’s everyday spectacles, but I’m still not sure I would recommend it for this as, solely in my opinion, they seem to change the colour of things slightly making everything look a little sepia, which I personally don’t like. But they are certainly more restful on my eyes – when I’m using my computer, phone or tablet (or watching the TV late at night with the lights out – naughty, naughty!).

.jpeg)

(Please excuse the "selfie"!)

As always, if you have any questions about the topics discussed in this, or any of my other blog posts, please don’t hesitate to contact me! It would be great to hear from you!

Write comment (6 Comments)Page 5 of 16